Behind every protest chant, every policy demand, and every march for a better world, there lies a set of powerful, often invisible, philosophical ideas. Social justice movements do not emerge from a vacuum; they are born from profound arguments about the nature of right and wrong, the meaning of freedom, and the definition of a just society. Philosophy is not a detached academic exercise; it is the "source code" for revolution and reform. This article uncovers that code, tracing the direct line from the quiet contemplations of philosophers to the thunderous calls for change that have shaped our history

Key Points

- Philosophy provides the essential "why" for social justice movements by defining core concepts like justice, equality, and human rights, which form the moral and logical foundation for activism (1).

- Enlightenment philosophy, particularly John Locke's theory of "natural rights" (life, liberty, and property), provided the ideological justification for the American Revolution, abolitionism, and early civil rights struggles (2).

- Utilitarianism, developed by Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill, influenced movements for women's suffrage and animal rights by arguing that a just society is one that minimizes suffering and maximizes well,being for the greatest number (3).

- Karl Marx's philosophical critique of capitalism, focusing on concepts of "alienation," "exploitation," and "class struggle," became the foundational text for labor movements, socialist revolutions, and anti,colonial activism worldwide (4).

- 20th,century philosophy, including Simone de Beauvoir's "Existentialist Feminism" and the development of "Critical Theory" and "Intersectionality," provided the tools to deconstruct social roles and analyze how systems of oppression overlap, underpinning modern feminist and anti,racist movements (5).

Introduction: The Source Code of Revolution

Behind every protest chant, every policy demand, and every march for a better world, there lies a set of powerful, often invisible, philosophical ideas. Social justice movements do not emerge from a vacuum; they are born from profound arguments about the nature of right and wrong, the meaning of freedom, and the definition of a just society. Philosophy is not a detached academic exercise; it is the "source code" for revolution and reform. It provides the language to articulate injustice, the framework to critique power, and the vision to imagine a different world.

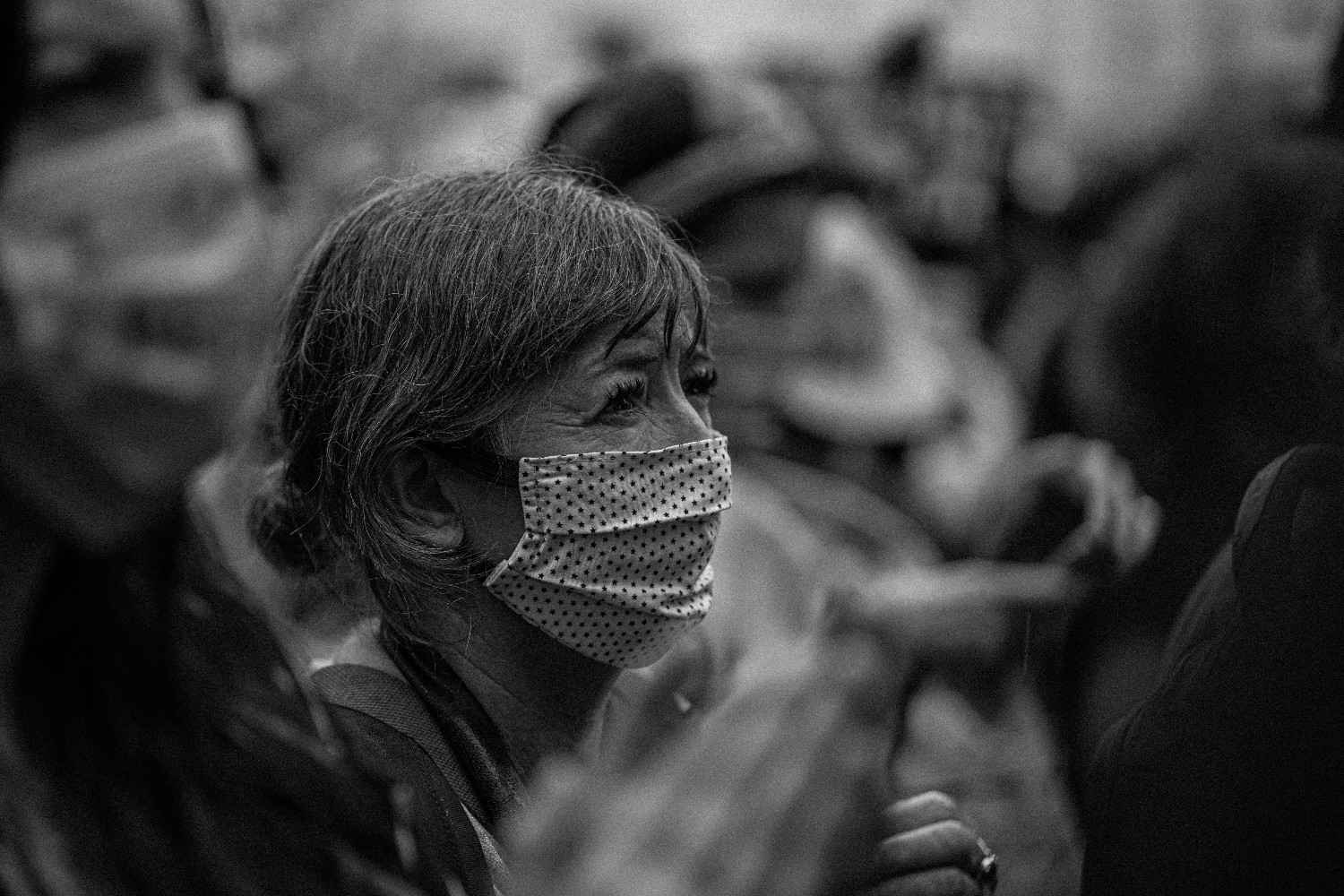

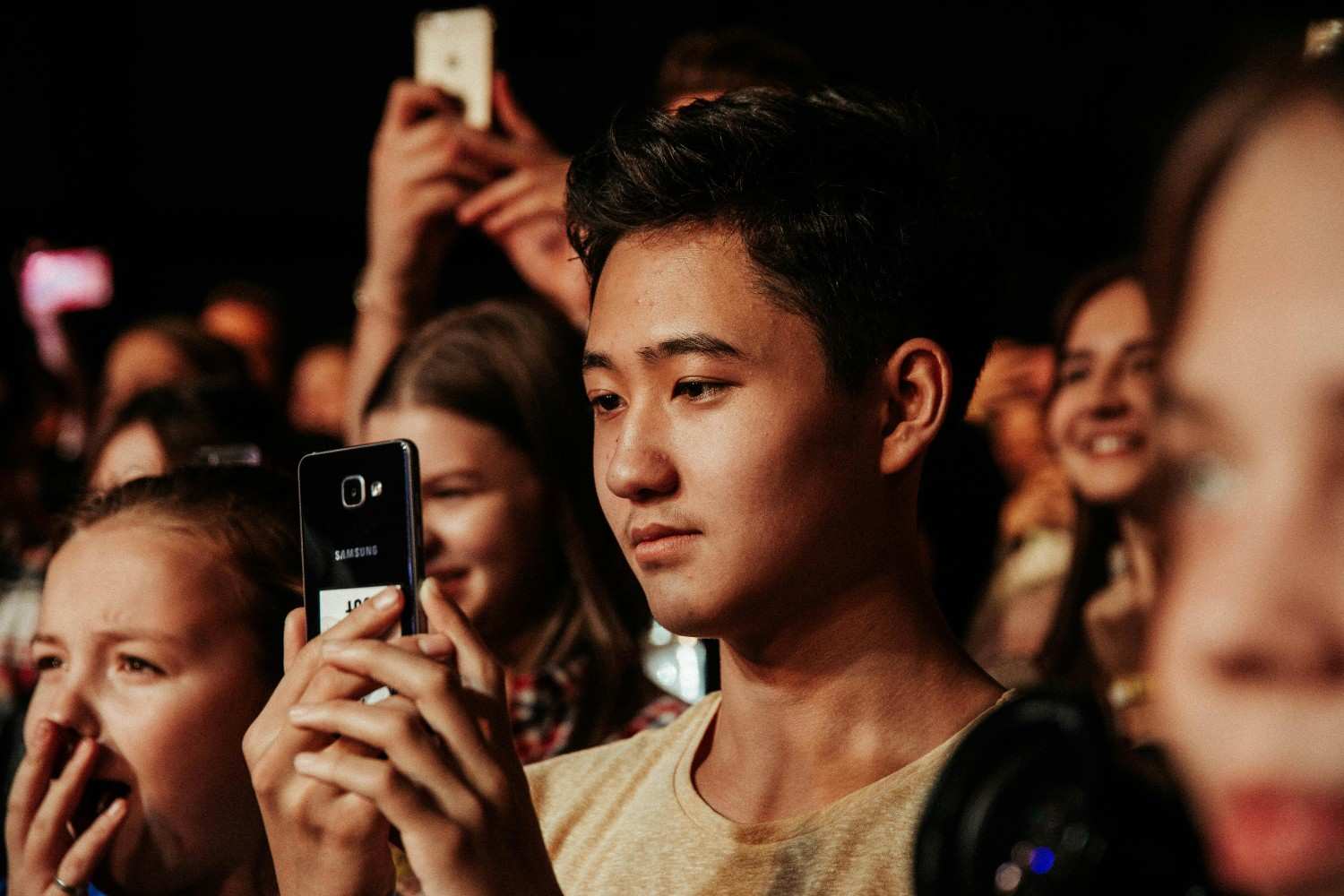

When abolitionists argued against slavery, they were not just expressing emotional outrage; they were wielding the philosophical language of natural rights. When suffragettes demanded the vote, they were building on ethical arguments about equality and utility. And when modern activists talk about intersectionality, they are engaging with a deep philosophical tradition of deconstructing power. This article, by social philosopher Dr. Anya Sharma, will uncover that source code. We will trace the direct line from the quiet contemplations of philosophers to the thunderous calls for change that have shaped our history, demonstrating that to truly understand a social movement, you must first understand its philosophical heart. This connects deeply with our discussions in articles like Exploring Intersectionality and Moral Relativism (6). All information is current as of September 16, 2025, at 09:45 AM GMT.

The Blueprint of Justice: What is Philosophy's Role?

Before we examine specific movements, it is crucial to understand "what" philosophy actually provides for activists. Its role can be broken down into three essential functions:

- It Defines the Goal. A movement needs a destination. Philosophy helps define what "justice," "equality," or "freedom" actually mean. Is justice about equal opportunity or equal outcomes? Is freedom the absence of constraint, or the presence of genuine choices? Philosophers like John Rawls, with his "veil of ignorance" thought experiment, provide conceptual tools to build a vision of a just society, giving movements a clear and defensible goal to strive for.

- It Provides the Justification. A movement needs a reason. Philosophy provides the moral and logical arguments for "why" the current state of affairs is unjust. It moves the conversation from "I don't like this" to "this is wrong, and here is why." By identifying violations of rights, failures of social contracts, or systemic harm, philosophy gives a movement its moral authority and its intellectual backbone.

- It Critiques Power. A movement needs to understand its opponent. Philosophers, from Plato to Foucault, have been analyzing the nature of power for centuries. They provide the tools to look beyond individual "bad actors" and see how injustice is embedded in systems, institutions, and even language itself. This allows movements to target the root causes of a problem, not just its symptoms.

In essence, activism is the "how," but philosophy is the "why." Without a coherent philosophical foundation, a movement is merely a collection of grievances; with one, it becomes a force for coherent, principled change.

The Enlightenment and the Birth of "Rights"

Perhaps the most potent philosophical idea ever gifted to social justice movements is the concept of "natural rights." Before the Enlightenment of the 17th and 18th centuries, authority was typically justified by divine right or brute force. But philosophers like John Locke (1632,1704) introduced a revolutionary idea: that human beings are born with certain inalienable rights, simply by virtue of being human. For Locke, these were the rights to "life, liberty, and property."

This was a seismic shift. It meant that the rights of an individual did not come from a king, a government, or a god; they were inherent. Therefore, the purpose of government was not to "grant" rights, but to "protect" the rights that people already possessed. If a government failed to do so, it was illegitimate, and the people had the right to rebel.

The impact of this idea was immediate and explosive. It became the central justification for the American Revolution, as Thomas Jefferson famously paraphrased Locke in the Declaration of Independence, citing "unalienable Rights" to "Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness." But its influence did not stop there. This same philosophical language became the most powerful weapon for the abolitionist movement. Activists like Frederick Douglass brilliantly exposed the profound hypocrisy of a nation that claimed to be founded on natural rights while enslaving millions. He argued that the rights Jefferson spoke of were not just for white men, but were the birthright of "all" humanity. By using the Enlightenment's own philosophical tools, abolitionists demonstrated that slavery was not just a cruel practice, but a direct contradiction of the nation's founding principles.

The Utilitarian Calculus: Minimizing Suffering for All

Another powerful philosophical engine for social change was Utilitarianism, developed in the 18th and 19th centuries by thinkers like Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill. Its core principle, the "Greatest Happiness Principle," is simple but profound: the most ethical action is the one that produces the greatest amount of good and minimizes the greatest amount of suffering for the "greatest number" of sentient beings.

This framework shifted the focus of morality from abstract duties or rights to the real,world consequences of actions. This had two major implications for social justice.

First, it blew the doors open for the "animal rights" movement. Before Bentham, arguments about our duties to animals were often dismissed because animals could not reason or speak. Bentham's famous retort cut through this: "The question is not, Can they reason? nor, Can they talk? but, Can they suffer?" If the basis of morality is the prevention of suffering, and animals can clearly suffer, then their suffering must be included in our moral calculations. This single philosophical insight remains the bedrock of the modern animal welfare and animal liberation movements.

Second, John Stuart Mill, in his seminal work "The Subjection of Women" (1869), applied utilitarian logic to argue for "women's suffrage" and equality. He argued that the legal and social subordination of women was not just an injustice to them, but a detriment to "all of society." By preventing half the population from developing their talents and contributing to public life, society was robbing itself of an immense source of happiness, innovation, and progress. Granting women equal rights was not just a matter of justice for women; it was a necessary step to maximize the well,being of humanity as a whole.

Marxism and the Struggle for Economic Justice

No philosophical theory has had a more direct, explicit, and explosive impact on social movements than that of Karl Marx (1818,1883). Marx provided more than just a critique of injustice; he offered a complete theory of history, a deep analysis of economic power, and a call to revolutionary action.

Marx's philosophy of "historical materialism" argued that the driving force of history is the struggle between economic classes. In the capitalist era, this was the struggle between the "bourgeoisie" (the owners of the means of production) and the "proletariat" (the working class). He introduced powerful concepts to describe the injustice of this system:

- Exploitation: The idea that capitalists extract "surplus value" from workers, paying them less than the actual value their labor creates.

- Alienation: The feeling of powerlessness, meaninglessness, and estrangement workers feel from their own labor, from the products they create, from each other, and from their own human potential.

This philosophical framework was transformative. It gave workers around the world a language to understand their shared experience not as a series of individual misfortunes, but as a systemic problem baked into the very structure of capitalism. It became the intellectual foundation for the "labor movement," the formation of unions, the fight for the eight,hour workday, and the demand for safer working conditions. It also, of course, fueled socialist and communist revolutions across the globe, from Russia to China to Cuba, fundamentally reshaping the political map of the 20th century.

Deconstructing Power: From Existentialism to Intersectionality

The 20th century saw a shift in philosophy's role, moving towards a deconstruction of more subtle forms of power embedded in culture, language, and social identity.

A pivotal moment was the rise of "Existentialist Feminism," most famously articulated by Simone de Beauvoir in her 1949 book "The Second Sex." Drawing on the existentialist idea that "existence precedes essence," which we discuss in our post on Existentialism, de Beauvoir made the groundbreaking claim: "One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman." She argued that "woman" is not a fixed, biological destiny, but a social construct, an "Other" defined in relation to "Man" as the default. This philosophical act of deconstructing gender provided the intellectual fuel for the second,wave feminist movement of the 1960s and 70s, which sought not just legal rights, but a liberation from oppressive social roles and expectations.

This focus on systemic power and social construction was further developed by the "Frankfurt School" of Critical Theory and, later, by American legal scholars who developed "Critical Race Theory." These philosophies examine how racism is not merely a matter of individual prejudice, but is embedded in legal systems and social institutions. This leads directly to the concept of "Intersectionality," coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw and explored by philosophers like Patricia Hill Collins. Intersectionality provides a framework for understanding that systems of oppression, like racism, sexism, and classism, do not operate independently but "intersect" and overlap, creating unique experiences of discrimination and privilege. This philosophical tool is central to many contemporary social justice movements, from Black Lives Matter to LGBTQ+ advocacy, allowing for a more nuanced and inclusive understanding of injustice.

Comparison: Philosophical Engines of Social Change

| Philosophical School | Core Concept | Social Justice Application | Example Movement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enlightenment Liberalism | Natural Rights | Argues for inherent, universal rights that governments must protect. | Abolitionism |

| Utilitarianism | The Greatest Happiness Principle | Argues for policies that reduce suffering for the greatest number. | Women's Suffrage, Animal Rights |

| Marxism | Class Struggle & Exploitation | Critiques economic systems as inherently unjust and oppressive. | The Labor Movement |

| Existential Feminism | Social Construction of Gender | Deconstructs traditional roles to liberate individuals from stereotypes. | Second,Wave Feminism |

| Critical Theory | Intersectionality | Analyzes how different systems of oppression overlap and interact. | Modern Intersectional Feminism |

Conclusion: The Unseen Architect of Change

Social justice is not philosophically neutral. Every demand for change, every critique of the status quo, is built upon a philosophical foundation, whether it is explicitly acknowledged or not. From the "self,evident" truths of the Enlightenment to the complex analyses of modern critical theory, philosophy has consistently served as the unseen architect of social transformation. It provides the moral clarity, the intellectual rigor, and the visionary power that turns a crowd of discontented individuals into a coherent movement for justice.

Today, as we confront new challenges like climate change, digital privacy, and global inequality, new philosophical work is being done to help us understand and address these issues. Philosophy is not a historical artifact; it is a living, breathing discipline that continues to evolve alongside our struggles. To be an effective advocate for a better world, it is not enough to be passionate; one must also be principled. Understanding the philosophical ideas that underpin the quest for justice is the first step toward building a movement that is not just loud, but lasting.

References

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Justice

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Locke's Political Philosophy

- Utilitarianism.net - John Stuart Mill

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Karl Marx

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Existentialist Feminism

- AIER - The Philosophical Underpinnings of Social Justice